The Lexical Funk!

Daniel has wanted to be a writer ever since he was in elementary school.He has published stories and articles in such magazines as Slipstream, Black Petals, Spindrift, Zygote in my Coffee, and Leading Edge Science Fiction. He has written four books: The Sage and the Scarecrow (a novel), the Lexical Funk (a short story collection), Reejecttion (short story/ essay collection), and The Ghosts of Nagasaki (a novel).

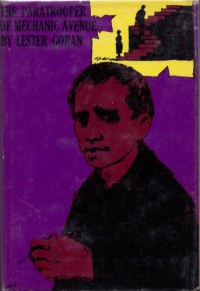

Review - The Paratrooper of Mechanic Avenue

I try to imagine Lester Goran a few years before this novel was published. This must have been 1956 or 1957. He's a struggling writer. He's reading the great works of fiction, pulling them apart and putting them back together again to see how they tick. He's in his mid-20s and he's desperately trying to write something worthy of his young ambitions.

Miraculously, The Paratrooper for Mechanic Avenue is accepted. The young man begins a career.

I typically think of first novels as failures. As learning experiences. Who knows if this was actually Lester's first novel. It certainly doesn't read like a first novel. After having read three other of Lester's works, works that were much easier to track down, here I am reading his first novel -- so I can pull it apart and put it back together again (as Lester did with the authors he read).

What do I learn reading this novel? I learn something about choosing subjects. A novel about an impoverished Polish family growing up in the ghetto -- this couldn't have been an easy thing to write about. It must have been an even harder sell. There are no clear heroes in this novel, but the characters are compassionately drawn. If their realism makes them ugly and hard to romanticize, Lester's sympathy for them also makes us care about them -- ugly warts and everything. Perhaps he had to write about this. The subject chose him. Not the other way around.

I learn about characters. Good characters should lead their authors as much, if not more, than their authors lead them. Ike-O, the failed soldier and child of a Polish ghetto, often leads the story in ways that are unexpected but realistic. His story and Dolly's story probably wouldn't fit into the neat boxes of a pre-fabricated plot outline. I think that makes this story stronger, not weaker. It also probably made it a harder sell to a literary agent. (The plot synopsis usually goes before the manuscript.)

Authenticity. Lester always said, you don't have to write what you know, but you can't write what you don't know. It's clear that Sobaski's Stairway is a real place. Catfish Gudunsky is a real person. The authenticity is what makes the novel.

First novels and the collective memory of literature. This was Lester's first novel -- published when he was 26. It's a triumph. At sixteen chapters and 178 pages, it might not be an ambitious artistic work. First novels shouldn't take too many bold risks. But within these confines there is clear genius. 56 years later, the book is all but forgotten.

It's not obvious that it should be. Sure, the novel is about ugly people in an ugly environment doing horrible things (so is most of Steinbeck's novels). The topic itself probably wasn't easy to market. But if good literature is supposed to naturally rise to the top, then there is no good reason to believe this book shouldn't still be with us today in some form.

Thus, the last thing I learned from the book is this: It's not enough to write good literature. It's not enough to read good literature and to try to emulate its practices. We also need to be advocates for good literature. We need to keep our eyes open for the neglected works and keep them alive whenever we can.

What do we miss if we don't? We miss moment like these:

"Ike-O did not look at him; the world pulls in on itself, it ends, it suffocates itself like a match gone out, and Ike-o Hartwell stands on the corner of Mechanic and Gardenia and looks away and asks no questions and waits dumbly to suffer further." (p. 143).